Ethnic-American Literature Class Exhibit

This exhibit was created by undergraduates in Dr. Andrew Uzendoski’s Fall 2018 Ethnic-American Literature course at Lafayette College. Student contributors to the exhibit put archival artifacts from the Easton NAACP-Sigal Museum Collaboration Collection into conversation with course texts in order to explore topics such as gender and culture, ethnic identity, privilege, and intersectionality. Exhibit entries examine change over time in the Black experience in Easton; the purpose of building the exhibit was for students to use literary texts as tools to examine major course topics in a local community context. Topics addressed by students include civic engagement, food culture, the military, and community youth organizations. Local NAACP affiliates Marvin Boyer and Clifford Ransom consulted with students as they built the exhibit.

Editing and layout by Julia Stomber.

NAACP Unit Told Racism Still Alive

By Madie Levine

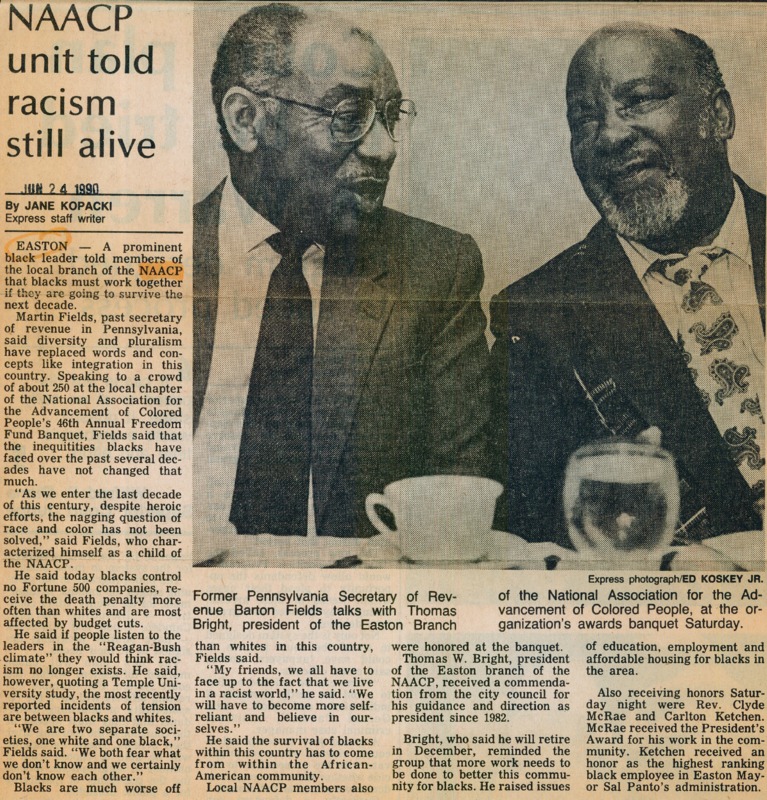

Although published almost 30 years apart, the sentiments regarding racism in the United States are virtually identical in James Baldwin’s letter “My Dungeon Shook” and an article in the Easton Express Times detailing an NAACP meeting led by former secretary of revenue in Pennsylvania Martin Fields. While Baldwin’s letter is a reflection of the fight for Civil Rights in the 1960s, the article, published in 1990, demonstrates how the same concerns and racial tensions described by Baldwin persisted throughout the decades following his passionate letter to his nephew. Martin Fields is reported in the article as preaching the same ideas and attitude towards racism as Baldwin did 30 years later. Both Baldwin and Fields express their disdain for the racism and inequality within their communities, stress the danger of the ignorance of white people, and encourage their respective audiences to overcome their situation by finding strength within their community.

The article, written by Jane Kopacki and titled “NAACP Unit Told Racism Still Alive” profiles an Easton NAACP meeting in which Martin Fields warns his community of the prevalence of racism in their society and encourages them to combat this racism by recognizing the ignorance of others, accepting and realizing the racism they face, and focusing on improving themselves and their self worth. In the meeting, the article quotes Fields as acknowledging the heroic efforts made by past activists over the last several decades, but asserts that the problems they protested and fought against still remain as they approach the turn of the century. Fields states, “today blacks control no Fortune 500 companies, receive the death penalty more often than whites, and are most affected by budget cuts … blacks are much more worse off than whites in this country” (Kopacki). The article contiunes on to describe Fields' encouraging remarks towards his community; specifically, not to be discouraged by the racism that exists in society, but rather use it as fuel to motivate themselves and find confidence and strength within themselves. Fields reiterates that the racial inequalities faced by activists in decades past are still not rectified, and that he believes it is time for the Black community to come together, recognize the issues and limitations they face, and work towards a racial equality in society.

The most compelling connection between Baldwin and Field’s testimonies is their mention of the ignorance of the existence of racism by some of the white population. Baldwin warns his nephew that many perpetrators of racism do not believe they are racist and are unaware of the danger and harm they inflict onto the black community. He claims that many white people hold onto a sense of false innocence; forgetting the brutal racism that was carried out by their ancestors and how it still persists in the current time period. He warns his nephew that it is not the outward malice of these white people that perpetuates these racial conflicts, but their failure to accept history and that recognize the deep-rooted prejudice and racism that has been regarded as the norm for hundreds of years. Like Fields, he emphasizes that he has seen no improvement in society and blames the ignorance of “these innocent and well-meaning [white] people” (Baldwin 2). Baldwin describes the black experience as similar to its counterpart a hundred years ago, prior to the Emancipation Proclamation. He writes, “your countrymen have caused you to be born under conditions not very far removed from those described for us by Charles Dickens in the London of more than a hundred years ago ... I hear the chorus of the innocents screaming, 'No! This is not true! How bitter you are!" (Baldwin 2). Similarly, in the article, Fields is quoted as preaching a similar idea 30 years later, and blames the political leaders of the time for this issue of racial ignorance. He claims that if people listened to the leaders in the Reagan-Bush era, they would all think racism no longer exists. Fields attributes the ignorance of influential figures as the cause of continued segregation and racial tension, stating, “we are two separate societies, one White and one Black ... we both fear what we don’t know and we certainly do not know each other" (Kopacki). Both Baldwin and Fields repeatedly identify this ignorance as damaging to society and both offer solutions that come from within the black community.

In Baldwin’s eyes, because white people of his time are “trapped in a history which they do not understand” at no fault of their own, it is the responsibility of the black man to accept the white man; not the other way around (Baldwin 3). The article depicts Fields as portraying a near identical mentality - “he said the survival of Blacks from within this country has to come from within the African American community” (Kopacki). Both Baldwin and Fields believe that the problem of racism in the United States must be combated by the black community from a place of love, acceptance, and dignity. Both face racism in their society but use their voice to encourage their community to take the higher road and find the strength within themselves to improve their situation. While Baldwin explicitly tells his nephew to help white people be free before black people can be, Fields does so more inadvertently, telling the Easton branch to find confidence, self-worth, and strength to overcome the hindrances placed on their race.

The thoughts of Fields and Baldwin, though written almost 30 years apart, focus on a similar testimony regarding race; more specifically, the danger of the ignorance of racism. Both men implore their audiences to accept and recognize the persistence of racism and the presence of it in their lives. Fields and Baldwin both see a solution coming from within the black community and hope that they can inspire others to channel their individual worth to eventually reach a place of racial harmony and surpass the disadvantages and prejudices placed on their race.

Works Cited

Baldwin, James. "My Dungeon Shook: Letter to My Nephew on the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Emancipation." The Fire Next Time. Ed. James Baldwin. New York: The Dial Press, 1963. 17-24. Print.

Living Life As A Second Class Citizen

By Syd. V.

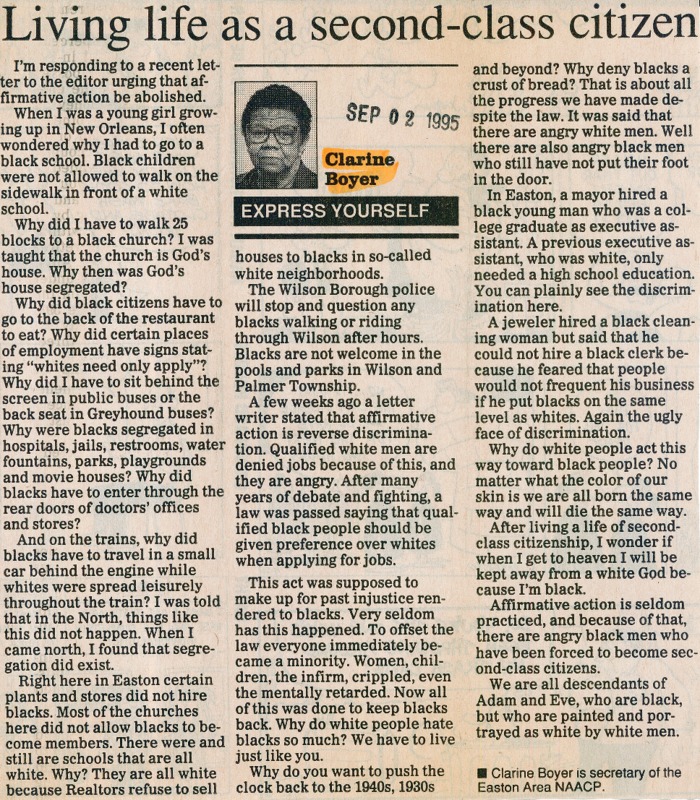

Clarine Boyer’s 1986 newspaper article explains the hardships and racism experienced by black Americans during the time, providing context and partial justification for the act of passing, as explained in Nella Larsen’s 1929 novel, "Passing". This newspaper article written by black female activist Boyer details the numerous struggles encountered by African Americans living in Easton, Pennslyvania. This artifact is one in a series of three essays, written by Boyer for the occasion of Black History Month. Published in the Easton Express Times, Boyer’s article is a first-hand look into the lives of black Eastonians, who have been subsequently labeled by society as second-class citizens. She cites examples of employment discrimination, wrongful imprisonment, and inequality in schools as just a few of the many injustices which existed in Easton in 1986. This account is incredibly important in understanding the racial climate of the time, which produced discriminatory practices of which black residents were forced to endure. Boyer explains how blacks have the lowest paying jobs, are denied positions on important city councils, and are continuously disadvantaged by the education system. This prevents them access to the resources necessary to rise into roles of power within Easton, which in turn, perpetuates their second-class status. Boyer’s article is a call to stop these discriminatory practices, and to allow African American residents the same freedoms and opportunities as the white Eastonians who were considered the first-class citizens. Though the article sheds a necessary light on the racial tensions during this time, it ends on an optimistic note. Boyer acknowledges that despite “intolerable odds,” the black population continues to endure and rise, led by such renowned figures such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Clarine Boyer’s article puts into context the act of “passing” which is detailed in Nella Larsen’s novel of the same name. The novel centers around Irene and Clare, two African-American women who are able to “pass” as white in society. While Irene chooses to live her life true to her African American roots, Clare uses her appearance to assimilate into white society, even marrying a white man who is actively racist. During this time, the practice of passing allowed African Americans access to the resources and privileges of white society, though it meant they were forced to give up their ethnic identity. Clare herself wonders “why more colored girls … never ‘passed’ over ... it’s such a frightfully easy thing to do” (Larsen 16). The examples of racist behavior and injustice described in Boyer’s article justify, in some ways, Clare’s choice to pass as white. We see examples of the same racially charged behaviors in Nella Larsen’s writing, specifically endured by Irene, who presents as an African American. Irene is forced to pass herself when she goes out into white society, so as to not receive unfair treatment by white citizens.

By choosing to pass as a white woman, Clare is able to avoid these discriminatory behaviors for herself and her daughter, allowing them both the ability to climb the social ladder of society. It also allows them to exist in white society without scrutiny, and to have access to important educational, opcupational, and social resources that white citizens have enjoyed for centuries. However, Clare is also robbed of her sense of self, and with it her potential power to be a strong voice for change in the black community. She is essentially “caught between two allegiances” and is subsequently teaching her daughter that African Americans are second-class citizens, since she herself chose not to identify as one (Larsen 78). Boyer may have understood Clare’s reasoning for passing - she was attempting to provide herself and her child with a life free of discrimination in school, free of limited employment opportunities, and free of racial injustice, all of which were very much still prevalent in the 1960s. However, she also would have critiqued Clare’s choice to cast off her racial identity and assume one that so blatantly contradicted the ideas of the Civil Rights Movement. Boyer’s article chronicles the difficult life African Americans were forced to live as second-class citizens, which ultimately justifies why some individuals, including Clare in Larsen’s novel, would choose to pass in white society to avoid discrimination and racial injustices.

Works Cited

Larsen, Nella. "Passing". Wilder Publications, Inc., 2018.

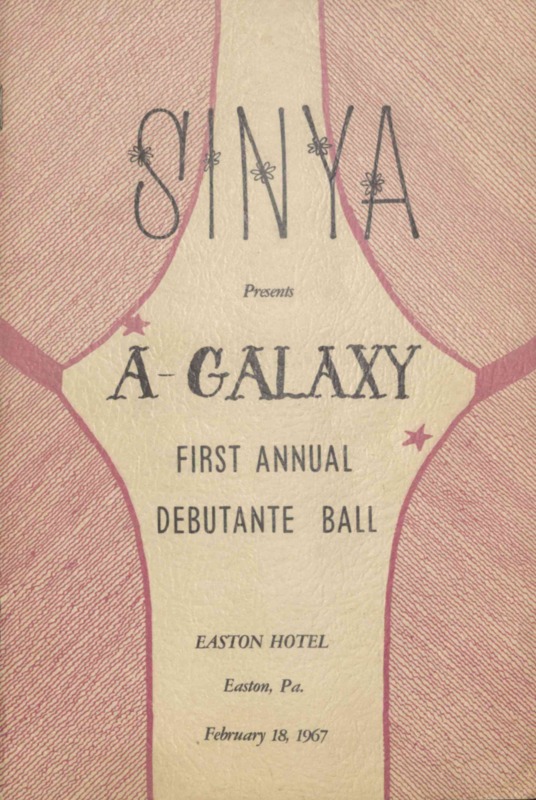

SINYA Debutante Ball 1967

By Zulaihat Yusif

The 1900s was a period rooted in establishing African American identity. It was a time to define what it meant to be black within the parameters set by African Americans instead of primarily existing to combat mainstream stereotypes and racial divides. A look at Nella Larsen's 1929 novel Passing and the Lehigh Valley Engaged Humanities Consortium (LVEHC) 1967 pamphlet depicting the first annual debutante ball by the Society for the Improvement of Negro Youth Activities (SINYA) highlights the conditions of the 1900s and how African American identity was formed. These texts depict the nuanced ways African Americans reproduced tropes of respectability through practices like debutante balls. SINYA presented the rationale for organizing these balls in the brief history section detailed in the pamphlet. The goals are underscored in the following excerpt:

In December, the girls were presented in beautiful fashions in a style show. Their poise and their beauty giving great evidence of why they were to be debutantes. Since the aim of SINYA is to assist these teenage girls in attaining high ideals through guided social and educational functions, they were all provided with the means in the form of eight professionally supervised workshops (SINYA).

Upon researching the debutantes, the professionally supervised workshops mentioned allude to a history of teaching proper etiquette. The young women who are to be introduced to society are to have a multitude of skills. For the purpose of this piece, the focus is on the young women knowing appropriate dress selections for occasions, interpersonal, and conversational skills. The mention of “beautiful fashion” signals a standard of appropriate attire. The section on “poise” and “beauty” places emphasis on outward appearances because that contributed to the overall image of a woman deserving of respect and acknowledgement as a debutante. Although these objectives are not explicitly stated, they reveal an underlying agenda that even the creators of the SINYA debutante balls may not have recognized or intended to reproduce.

Nella Larsen's "Passing" also illustrates each of the skills taught to the young debutante girls through Clare and Irene. These are two female characters invested in black elite society and their position as members of high society relies on them being compliant to attributes of respectable women. Despite the characters not explicitly stating they were debutantes, their development in the text and values are in line with the aims of SINYA. The first value discussed was appropriate dress attire. This is demonstrated when the protagonist Irene shares tea with women she grew up with. Irene describes:

Her overtrimmed Georgette crêpe dress was too short and showed an appalling amount of leg, stout legs in sleazy stockings of a vivid rose beige shade. Her plump hands were newly and not too competently manicured— for the occasion, probably (Larson 49).

The object of Irene’s critique is clearly that this woman is unsuccessful in presenting herself for the occasion. Her attire is defined as “too short". Irene criticizes the "appalling amount of leg”, revealing the strict standard in place for the quality of clothing. Irene's thoughts towards dress code are in line with SINYA’s education of dress code for the debutante balls. In the pamphlets, all but one of the young women are seen in long ball gowns covering themselves. Women who showed too much legs maybe presumed promiscuous or loose. Loose women were not respected because they strayed from the safe and socially acceptable norm. Even the young lady whose dress is shorter has a dress slightly below her knees. The women here have learned that their attire is appropriate to introduce them to their society in a way women deserving of esteem would. Irene’s statements suggest that since the woman is not appropriately dressed, she is not worthy of the same level of reverence as herself.

The SINYA debutante balls also also emphasized the need to have adequate table etiquette and entertaining skills. This is portrayed in Larson's "Passing" when Clare serves the tea. The scene is described in the following excerpt:

The teathings had been placed on a low table at Clare’s side. She gave them her attention now, pouring the rich amber fluid from the tall glass pitcher into stately slim glasses, which she handed to her guests, and then offered them lemon or cream and tiny sandwiches or cakes (Larson 49).

Clare is the one hosting the ladies for tea. She gracefully distributes the tea taking her time to meticulously distribute the tea’s contents to her guests. She is knowledgeable about which holders contain what and the order in which she should serve them. She even goes as far as offering complimentary finger foods. While tea etiquette may appear to be common information, the emphasis and delivery of this scene by Nella Larsen suggests the requirement that Clare prove herself capable of such skills. Knowledge of these things makes Clare homely. It suggests that she has the proper training to entertain. Women who cannot exhibit this section of knowledge are perceived as less than because they fail to meet the standard.

Another skill that is vital to a woman's success which could be developed through the SINYA debutante balls is the skill of interpersonal communication and conversation ability. This type is skill is also depicted by Irene and Clare in "Passing". Larson writes about it in the following excerpt:

Clare began to talk, steering carefully away from anything that might lead towards race or other thorny subjects. It was the most brilliant exhibition of conversational weightlifting that Irene had ever seen. Her words swept over them in charming wellmodulated streams. Her laughs tinkled and peeled. Her little stories sparkled (Larson 53).

Conversational skills here encompass maintaining light conversation that invites all to participate. Clare guides the conversation by avoiding “race” and “thorny subjects” to one that captivate her peers. Not only does she steer this conversation but she does so in a “charming” manner which allows her guests to appreciate her converational expertise. Had Clare failed to facilitate the conversation in this manner, she would move further away on the scale of respectability. Her failure looks like her having organic and authentic conversation but she is unable to do so because she has the task of ensuring the comradery of all those present. This is irrespective to her true nature and conversational interests, which takes second priority. This skill shows itself in the SINYA debutante ball, as the communication between the ball attendees, debutantes, and their escorts is a central feature.

In conclusion, it was expected that these skills allow the debutantes to move through spaces confident in their ability to adapt and interact with all manners of people. However, they compromise the integrity of their personhood within the delivery of respectable womanhood. If the actions and thoughts of these young ladies are not carried out in these methods, they lose that esteem in black high society. With the goals of the SINYA debutante balls defined in this manner and applied to Nella Larsen's "Passing", we get a toxic image of black social life and how its roots can originate in social and educational functions such as those of the debutante balls.

Works Cited

Larsen, Nella. "Passing". Wilder Publications, Inc., 2018.

Easton Makes Progress Up Ladder of Equality

By J. Vay

The archival artifact that I selected from the Lehigh Valley Engaged Humanities Consortium (LVEHC) Digital Archive is a newspaper article from the Easton Express Times titled, “Easton Makes Progress up Ladder of Equality.” This article, published on February 28, 1994, is written by Clarine Boyer, the secretary of the Easton Branch of the NCAAP at the time of publication. This article investigates this specific branch and the advancements the town has made towards integrating blacks into a white dominated society. Although Clarine Boyer makes an impact on the black community, she is comparable to Mrs. MacLane from the text “Flower Garden,” in that their efforts are noticeable and humanistic, but more must be done on a larger scale to reach equality for blacks.

Boyer begins her article by reflecting on a personal account, immediately establishing credibility to her readers. She notes that she has lived in Easton for forty-eight years, setting a time frame for how long she has been observing segregation in her community. When she first arrived, she claims that only four to five black people received professional jobs. Boyer continues to evaluate the minimal opportunities that were available for blacks in Easton. The jobs that were permitted included labor intensive work at the Bethlehem steel stacks or women working in sweatshops or factories. Furthermore, there was absolutely no black representation in the education systems. This is especially interesting because black students were allowed to attend school, but there were no black administrators, teachers, or staff. Not only were there no authority of color, but blacks were not even acknowledged as individuals in the school curriculum. One black student was suspended for protesting for a black history class. This student was one of twenty five others who were suspended in 1970 by the principal of Easton High School. Although there were retributions, these instances were crucial for the blacks' progressive movement. Boyer switches gears and boasts how the Easton Branch and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People began to fight for opportunities for black people after the Civil Rights Act was passed. Being the secretary of this branch, it is empowering that Boyer is a female of color and can still make such impactful changes. These new developments during the movement in Easton started with the hiring of two black supermarket cashiers. This then sparked Boyer and the rest of the branch to establish five days of black history programs, allowing for blacks to be fully integrated - becoming teachers, principals, nurses, store clerks, two attorneys, policemen, and firefighters. Additionally, Boyer’s son, Marvin, created the Easton Area Neighborhood Centers to continue to increase the successes of black individuals. Marvin spoke of his mother in class as assertive and powerful, which is can be clearly observed by the tone in this article.

Although Boyer is gratified to see such progress, this was still not enough. The legal system ignored all black on black crime, blacks were not represented on jury duty, and the court presumed that blacks were the criminals in cases and never the victims. Boyer’s article describes such an uplifting timeline, where the black community has climbed up the ladder, but unfortunately they are still far from the top.

This ladder analogy and the efforts of Clarine Boyer are comparable to Mrs. MacLane’s determination in the “Flower Garden.” Mrs. MacLane, similar to Boyer, goes against societal norms to do an honorable act. The town ridicules and ostracizes Mrs. MacLane, yet she still allows a black boy, Billy Jones, to tend to her garden, regardless of the disapproval of her community (Jackson 1). Boyer stands up against racism, calling out her son for making demeaning remarks towards Billy and ultimately welcoming him to work for her (Jackson 1). Both Boyer and Mrs. MacLane are making steps towards change, and are both climbing up the ladder, yet there is still more group work that must be done to reach the top. Clarine Boyer makes immense progress towards ending segregation, yet she remarks how blacks cannot be fully respected in society without the support of the law and the government. Similarlly, Mrs. MacLane continues to stick to her morals and keep Billy as a worker, even as her friends Mrs. Winning and Mrs. Burton laugh at her (Jackson 2). The society Mrs. MacLane lives in must rally around her in order for blacks to be fully integrated into her white Vermont community, and ultimately into society as a whole.

This archival artifact, a newspaper article from the Easton Express Times titled, “Easton Makes Progress up Ladder of Equality,” displays how Clarine Boyer and the Easton Branch’s efforts are productive, but that the search for equality overall is a long and agonizing process. Like Mrs. MacLane, Clarine Boyers remains loyal towards her beliefs and towards her ethical duties, acting as a step up the ladder and a contributing force towards equality.

Works Cited

Jackson, Shirley. “Flower Garden.” The Lottery and Other Stories, Camden, 2012.

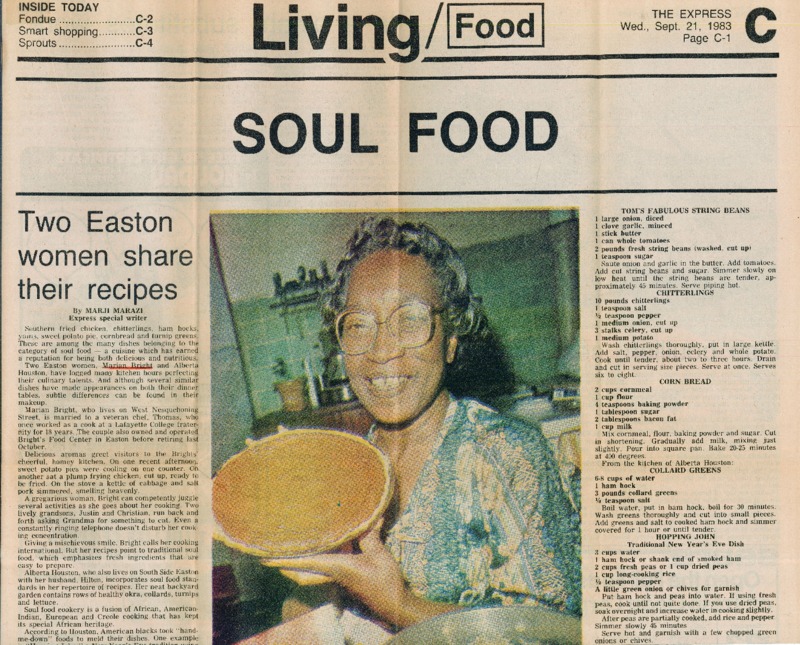

Soul Food

By Brandon Posivak

I chose to analyze an Easton Express Times article written by Marji Marazi in 1983 titled "Soul Food" . The purpose of the article was to share the special food recipes of two native Easton women, Marian Bright and Alberta Houston, with the rest of the Easton community. I chose to connect Marazi’s article to a scene from Nella Larsen’s "Passing" where Brian discusses his anguish over a lynching he read about in the newspaper during a family meal. Irene responds with frustration as such topics are not to be discuessed at the dining table. In both Marazi’s article and in "Passing", food is used as a tool of unification, and the dining table is used as a peaceful sanctuary for a family and a community during a time of increased racial tensions between blacks and whites. Marazi writes her article with an informative tone and dually appeals to food connoisseurs with the myriad of recipes present in the article as well as any individuals interested in cultural diffusion. Aside from the brief background on Marian Bright and Alberta Houston, Marazi’s inclusion of the recipes and images can help to educate her audience on the meaning of “Soul Food” as well as the proliferation of African American culture in the United States. The article features an image of Bright holding up a pie and smiling in the center. Marazi also details how to make many of Bright and Houston’s delicious recipes while specifying their cultural backgrounds as well. The term “Soul Food” is left up to the interpretation of the reader in the article, but Marazi does include that “Bright calls her cooking international” and that Houston’s cooking “blends Creole, American-Indian, and European elements with her African heritage” (Marazi).

Despite Nella Larsen’s "Passing" being written in 1929 in the midst of the Great Depression and Marazi’s article in the Easton Express Times being written in 1983, the two works share a series of parallels centered around race and food. The dinner table scene from "Passing" involving Brian and Irene fighting over what is considered appropriate at the dinner table highlights the idea that the dinner table is a sanctuary of peace, and food is used to unite the family. Larsen details how “after the boys had gone up to their own floor, Irene said suavely: ‘I do wish Brian that you wouldn’t talk about lynching before Ted and Junior ... it was really inexcusable for you to bring a thing like that up at dinner ... there’ll be time enough for them to learn about such horrible things when they’re older” (Larsen 191). Brian and Irene’s fight may have been centered around race, but Irene’s side of the argument was rested upon the idea that the dinner table and her cooking is a space separated from the hardships of reality.

Irene defended her belief that the dinner table and her cooking as a way to unite her family. Regardless of the day her children or her husband may have had, and regardless of the racism her family may encounter, Irene can create a sanctuary for her family through her cooking. Similarly, Marian Bright and Alberta Houston used their cooking to unite their families together around a meal consisting of soul food. Through her article, Marazi was able to share Bright and Houston’s cooking with the rest of their Easton community, further uniting people through food and family-centered meals. Using Bright and Houston’s recipes from “Soul Food”, Marazi gave the Easton community the opportunity to enter a sanctuary through food and to forget about any racial tensions that were prevelant during the time of the article's publication. In Larsen's "Passing" and Marazi's "Soul Food", food is used in both works as a method for the individuals to escape from their present situations and share happy moments with their families and communities.

Works Cited

Larsen, Nella. "Passing". Wilder Publications, Inc., 2018.

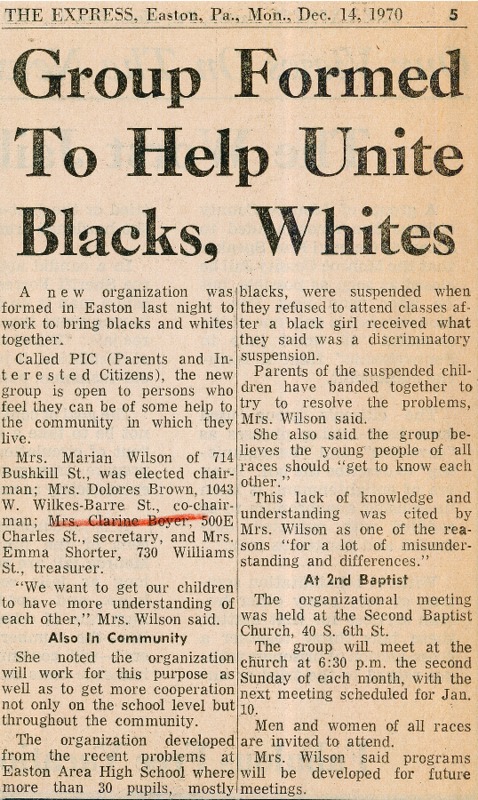

Group Formed To Help Unite Blacks, Whites

By Aditi Desai

The interaction between history and literature is a phenomenon that holds much value because it provides a basis for understanding how societal problems may be examined, addressed, and ultimately resolved. One such problem is the division that exists between distinct racial communities in America, which is brought to light both in literature and throughout history. Right here in Easton, for instance, the article “Group Formed To Help Unite Blacks, Whites,” published in 1970 in the Easton Express Times, proposed an initiative to begin bridging the gaps between formerly divided racial communities that coexist in the city. From a literary standpoint, John Okada’s "No-No Boy", is an example of a novel that explicitly highlights the separation of the Japanese-American community from other communities and calls for a change. The interaction between these pieces is important to examine because they both stress the same ideas about overcoming racial divisions: that the best way to start moving towards acceptance and understanding is to eliminate barriers, and that it is the youth of these communities who ultimately have the power to achieve this.

The article “Group Formed To Help Unite Black, Whites,” was published in the Easton Express Times on December 14, 1970 following the creation of the organization Parents and Interested Citizens (PIC), a reaction to problems at Easton Area High School. As the article describes, a group of “more than 30 pupils, mostly blacks, were suspended” after staging a walk-out and refusing to attend classes (Easton Express Times). Marvin Boyer provided more context when he described the social context during this period of time – in the 1960s and 1970s, racial tensions were high between the white and black communities of Easton, particularly in the high school. Given this background, he explained that the walk-out was a reaction to a fight that took place between two females, one black and one white – only the black girl received a suspension while the white girl was not punished, which many students felt was discriminatory.

According to the article, the parents of the suspended students decided to take action to bring to light and resolve some of the issues affecting the school. The intention of PIC was to have “young people of all races ... get to know each other” with the reasoning that the underlying source of many of the problems and misunderstandings that occurred between the two races was the lack of knowledge about each other’s racial communities (Easton Express Times). The group stated its purpose as looking to foster cooperation at both the school level and in the community of Easton as a whole. The members of the board – which included Mrs. Marian Wilson, Mrs. Dolores Brown, Mrs. Clarine Boyer, and Mrs. Emma Shorter – were all women who were activists in the community at the time. All residents of Easton, men and women, of all races, were invited to attend the meetings, highlighting the desire to start overcoming the divisions that had persisted over time in the city.

The connection between the race-related topics of this historical artifact and the novel "No-No Boy" may not seem obvious at first, but looking closer, it is evident that similar themes of divisions between races – and in particular, eliminating those barriers – are present in both. The novel, first released in 1957, tells the story of Ichiro, a Japanese-American man living during World War II who refuses to fight in the army. In the book, Ichiro struggles to re-integrate himself into American society after the war is over, both within the Japanese-American community and in the United States as a whole.

In the middle of the novel, Ichiro receives advice from his friend, Kenji, to marry outside the Japanese-American community. His belief is that the only way to break down the barriers between communities is to stop isolating themselves and start uniting with other groups. In Kenji’s mind, “living in big bunches and talking Jap and feeling Jap and doing Jap [is] just inviting trouble” because it is essentially accomplishing the same segregation that the government’s internment camps did, except this time it is self-imposed (Okada 163). When Ichiro points out that other communities, like “the Jews, the Italians, the Poles, the Armenians,” do the same, Kanji tells him “that doesn’t make it right” (Okada 164). This intentional self-separation manifested throughout the country; in particular, a similar phenomenon persisted in Easton in the 1960s and 1970s between the black and white communities. Kenji’s reaction to his situation is analogous to the reaction of the people who founded PIC – to try and fix these rifts. By advising Ichiro to separate himself from the Japanese-American community through marriage, Kenji is suggesting that Ichiro needs to start trying to learn about and understand different racial groups, as well as teach other groups about Japanese-Americans. This connects directly to PIC’s initiative to foster understanding and community-building across races to remedy understanding and strengthen the overall community of Easton.

An additional tie that exists between the article from 1970 and "No-No Boy" is the factor of age and the targeting of youth. While he is talking to Ichiro and offering him for about the future, Kenji specifically mentions the differences between generations and how age plays a role in how successfully the gaps between races can be bridged. He asserts that the older members of racial communities “don’t know” and “don’t want any better,” and that it is “the young ones who know and want better” (Okada 164). His point here is that while the older generation is more likely to be resistant to change, younger people should actively work towards shifting their perspectives and trying to understand groups outside of their own. Similarly, in Easton, part of PIC’s intention was to focus on young people and have them become more familiar with each other. In both cases, there is a recognition of the power that the younger generation has to spark change in their communities and in society as a whole. Ultimately, it is clear that both the article “Group Formed To Help Unite Blacks, Whites” and the novel "No-No Boy" teach readers related lessons about the importance of breaking down barriers that divide racial communities. Not only do they both stress that this is the first step to take towards fostering stronger understanding and tolerance of different groups, but they both also emphasize the vital role of youth in accomplishing this. Evidently, by examining historical artifacts in conjunction with literature, problems in society – as well as ways to address them – are brought to light and allow for the possibility of taking strides towards a more well-informed and tolerant world.

Works Cited

Okada, John. "No-No Boy". Combined Asian American Resources Project, 1977.

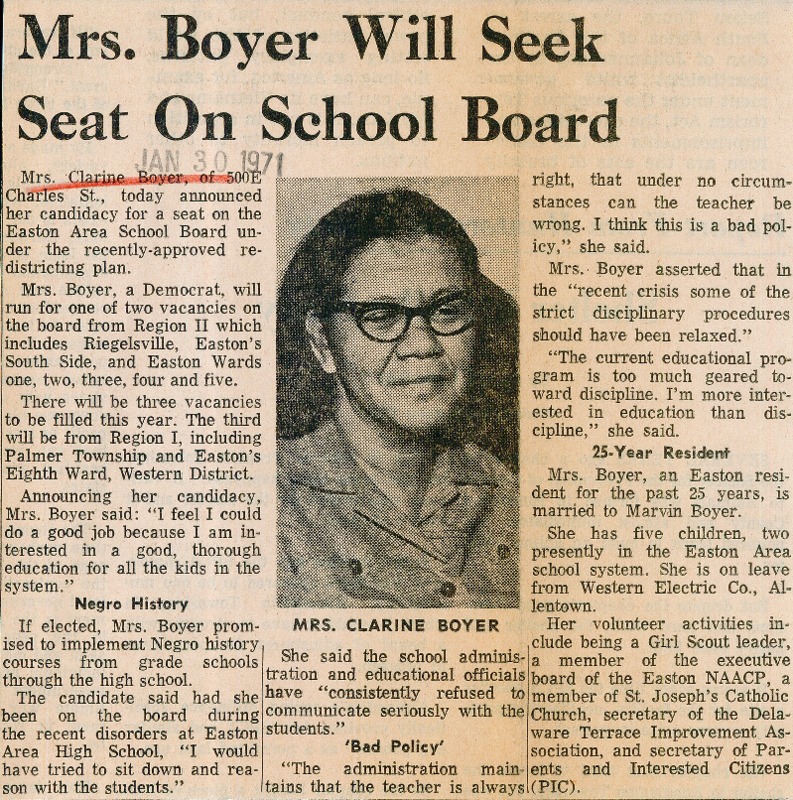

Mrs. Boyer Will Seek Seat On School Board

By Ryan O’Gorman

This artifact, published by the Easton Express Times on January 30th, 1971, is about an African American woman by the name of Mrs. Clarine Boyer, who is running for a position on the school board in Easton. The article gives her resumé and mentions many of her previous involvements within the community. It also provides three major points as to why Clarine Boyer is running for a position on the school board. The first point that Mrs. Boyer uses for her campaign is her implementation of “Negro History” in all courses from grade school to high school. This implementation is intended to reduce the prominent factor of whiteness that exists in many school systems. Mrs. Boyer also argues about how there is “Bad Policy” that exists in the current school system because it enforces a tactic where the teacher is always correct. Boyer argues against this “Bad Policy” - indicating that having an open mind is better in terms of fostering learning for students. Boyer discusses more of this “Bad Policy” throughout the article, stating that "the current educational program is too much geared toward discipline ... I’m more interested in education than discipline” (Easton Express Times). The final campaign argument that the newspaper article discusses is the significance of Boyer’s twenty-five year residency in Easton. Her work and Easton-related Contributions included being a Girl Scout leader, being a member of the NAACP, being a member of St. Joseph’s Catholic Church, and having a background of being a secretary. Mrs. Boyer had many qualifications to join the Easton School Board, and bringing equality for African Americans in the school system would hopefully improve as a result of her election.

As discussed, the archival article of Mrs. Clarine Boyer running for a position on Easton’s school board as an African American woman shows a perspective of someone who wants change for the equality amongst races. In the short story “It’s That It Hurts”, Tomás Rivera portrays the life of a Mexican student of color and his experiences with ‘whiteness’ in the school system. As previously described, Clarine Boyer is running to be on the school board because she believes that change is necessary in certain components of the classroom. In the short story it becomes evident that change is necessary simply because the treatment of minority students in comparison to white students is unacceptable. The opening phrase of the short story is, “it hurts a lot ... that’s why I hit him” (Rivera 83). This shows that racism in the school district affects a student’s attitude and can prevent them from learning at their full potential. Following the protagonists incident of punching a white boy in this short story, the boy gets expelled and is no longer able to go to school. There is an immense similarity in what Clarine Boyer said in her argument and the circumstance with the boy punching the white student. In the short story Mrs, Boyer's “Bad Policy” can be observed; it is shown as the teachers in school believed and practiced the concept of white supremacy. This means that they only saw one side of the story of the fight based on their preconceived notions about other races. Also, the disciplinary route of kicking this boy out of school permanently leaves him with no opportunity to receive an education. As Clarine Boyer campaigns, different strategies should be implemented rather than discipline as everyone deserves to keep being educated. The boy concludes that it is embarrassing that he got kicked out of school for punching a white boy, and he doesn’t know how to tell his parents about it. He likely doesn’t know how to tell his parents about the issue because racism is such a confusing topic for a young boy in elementary school to grasp. In the second paragraph of the short story, the boy looks at the positives of being expelled from school when he says “I thinks it’s better staying here on the ranch, here in the quiet of this knoll … where you at least feel more free, more at ease” (Rivera 83).

Clarine Boyer ran for a spot on the Easton School Board so children can in fact feel more free while being educated. Situations similar to the one described in Rivera’s short story should be prevented, and progress could have be made by diversifying the school board and using the campaign tactics presented by Mrs. Boyer. Everyone should be treated equally in the school system regardless of their race, and Mrs. Boyer had clear intentions to make that happen while being on the Board.

Works Cited

Rivera, Tomás. "It's That It Hurts." And The Earth Did Not Devour Him, Arte Público Press, 2015.

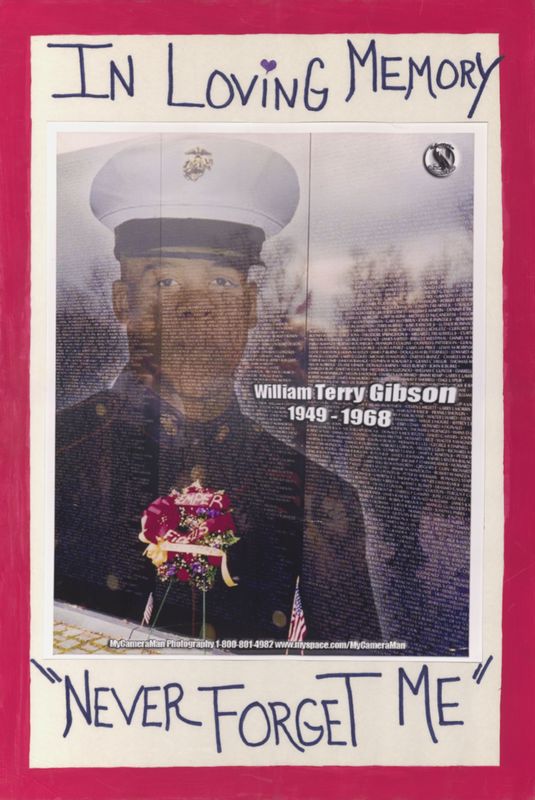

William Terry Gibson Memorial Poster

By Bryan H.

Printed on a white poster with a red border is a picture of a young African American marine. Behind this image are thousands of names of the men and women who served in the Vietnam War. On the top and bottom of this poster are two quotes: “In Loving Memory” and “Never Forget Me.” Pat Wheeler-Gibson and Julius Lockhart created this poster after the Vietnam Memorial in order to honor their lost loved one.

In John Okada’s "No-No Boy", Okada illuminates the difficulties experienced by a young Japanese man after answering "no" to the two questions that would grant him military service in the United States. Although William and Ichiro ultimately chose opposite paths in regard to military service, both the book, as well as the memorial poster, highlight the difficulties of war, two different perspectives of how one decision can have a lasting legacy, as well as an insight to the contrasting reasons behind joining or not joining the military.

William "Terry" Gibson’s name is engraved on panel W56, line 21 of the Vietnam Memorial. His name is surrounded by 57,938 other men and women who served in the Vietnam War. William Gibson, who was born on September 17, 1949 in Steubenville Ohio, attended Easton Area High School where he would become a co-captain for the wrestling team from 1966 to 1967. According to Marvin Boyer, Gibson had the potential to continue his athletic career and wrestle at the college level but decided to put that future aside and enlist in the Marines just like his father had done. His military service began at Parris Island and his first tour of duty commenced in Vietnam on June 9th, 1968. Gibson died in battle as a result of “enemy small arms fire while he was stationed in the Quang Tri Province in the Republic of South Vietnam on a jungle rat hole referred to as Phui Nui”.

Gibson passed away on June 18, 1968 when he was just 18 years old. This young man’s deployment lasted only ten days. His body is interred at the Easton Cemetery but his sacrifice and service lives on forever. Gibson earned the purple heart, combat action ribbon, Vietnam service medal, and many more through his loyalty and the courage he put forth to defend his country. His everlasting legacy is illuminated through the quote at the bottom of the poster which states, “Never Forget Me”.

When war presents itself, there are many factors that can affect your decision to serve or not. William Gibson and Ichiro Yamada, the protagonist of Okada’s novel, both made very different decisions regarding the military and serving the United States of America, but both decisions would impact them, as well as their families for the rest of their lives. It is evident that the main reason Ichiro denied the draft was because of his Japanese ethnicity and his families origin. Okada writes, “two weeks after his twenty fifth birthday, Ichiro got off a bus at Second and Main in Seattle ... he had been gone four years, two in camp and two in prison … he felt like an intruder in the world to which he had no claim … he had stood before the judge and said that he would not go in the army” (Okada 3). This passage highlights that for Ichiro, it was very difficult to agree to defend a country that once alienated him. Okada emphasizes that Ichiro believed he should have no sense of loyalty for a country who tried to make him not exist. During a conversation between Ichiro and an employer, the protagonist states, “first they jerked us off the Coast and put us in camps to prove to us that we weren’t American enough to be trusted ... then they wanted to draft us into the army ... I was bitter-mad” (Okada 137). It is very difficult to side with and trust someone who pushes you away in times of peace but pleads for your help when things get difficult.

Joining the army is a great example of making a commitment to something much bigger than yourself. When one is faced with such a decision, he or she must honor that decision and not regret it. William Gibson had a very different transition into the military. For any American citizen, sacrificing your life to serve your country is one of the most respected and brave decisions a person can make. The pride of being an American citizen comes directly from the ones who are putting their lives on the line to protect this country. Because Ichiro was “a Japanese who breathed the air of America and yet had never lifted a foot from the land that was Japan” he was in a very perplexing situation (Okada 12). The way he was treated by his country eliminated any trust and sense of true citizenship. Ichiro didn’t experience this feeling of belonging to the Unites States that William Gibson possessed. It seems obvious that Ichiro believed he would not experience the purpose and honor that Gibson felt when he enlisted in the armed services. For Ichiro, joining the military would not be a decision he could honor and feel proud about.

While both men ultimately made different choices in regard to serving their country, both decisions created a lasting legacy that would be associated with them and their family for a long time. When Ichiro decided to answer “no” to both questions, “he felt stripped of dignity, respect, purpose, and honor” (Okada 12). He felt he was neither American or Japanese and was stuck pondering ways to reenter this “shattered world”. Sadly, Gibson did not make it back home, but he was remembered as a hero for his service while Ichiro was stigmatized in the novel. Both this book and memorial poster illuminate the difficulties and risks each man had to consider and accept when they made their final decision. Because of each man’s different sense of belonging to this country, their intrinsic motivations differed immensely, ultimately resulting in the varying decisions.

War presented William Gibson and Ichiro Yamada with a decision that would directly impact their reputation and future. Ichiro was forced to make a choice that he believed had no right answer, while Gibson chose on his own, to sacrifice a normal lifestyle and serve his country. While both men were American citizens, ethnicity and war distributed a different sense of belonging and citizenship and completely influenced the two responses.

Works Cited

Okada, John, and Karen Tei Yamashita. No-No Boy. Penguin Books, 2019.

For information regarding the life and legacy of William "Terry" Gibson:

http://eastonvietnammemorial.homestead.com/williamgibson.html